Schedule of all St. Petersburg theaters on

one page >>

Please enter theatre's name, actor's name or any other keyword

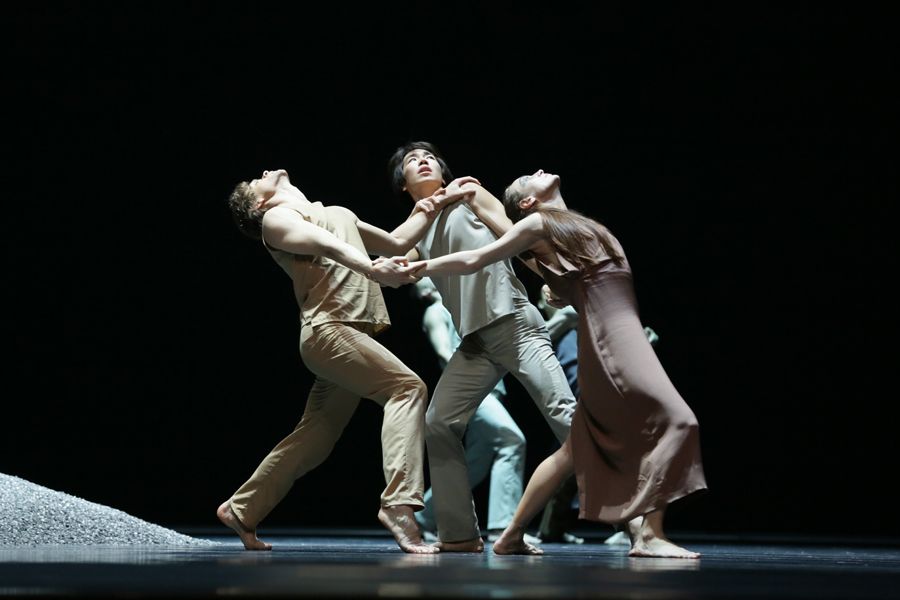

Sacre. Symphony in Three Movements (Mariinsky II (New) Theatre, ballet)

Genre: Ballet Age restriction: 6+

Credits

Music by Igor Stravinsky

Musical Director: Valery Gergiev

Choreographer: Sasha Waltz

Costume Designer: Bernd Skodzig

Stage Designers: Pia Maier Schriever, Sasha Waltz

Lighting Designer: Thilo Reuther

Assistant Choreographers: Juan Kruz Diaz de Garaio Esnaola, Luc Dunberry, Antonio Ruz and Yael Schnell

Co-production by Sasha Waltz & Guests GmbH and the Mariinsky Theatre

Artists

Cast to be announced

The history behind Le Sacre du printemps is the story of a challenge. Stravinsky’s music, which totally transformed views of composition technique and proved to be a breakthrough to new possibilities in music, was a challenge to the entire world’s professional experience. Nijinsky’s choreography with its approach to movement, its lack of correlation about the traditional ballet image of what is expressed and depicted heralded a new stage in the development of dance. The choreographer was drawn by the nature of ritual, the force of feeling the coming of spring and the terror of the insoluble and secret universe – the comprehension of the not so much externally formal components as the energetic message of the event. The rejection of the typical beauty of ballet was a challenge to refined audiences and the aestheticism of the World of Art. Since the premiere on 30 May 1913, when the audience was not ready for such a huge leap forwards, this challenge has remained an integral part of people’s ideas about Le Sacre du printemps. Each subsequent dance version of the score has been connected with the expectation of radical innovation. And the most significant of some two hundred dance versions of Le Sacre have provided revelations. Le Sacre du printemps proved to be a driving force in dance in the 20th century.

For any choreographer of the 21st century creating their own Sacre, the importance of the great productions of their predecessors and their significance on the world scale makes citations all but inevitable. Sasha Waltz’s production also includes numerous references to masterpieces of the past. In creating her own version in the year of the work’s centenary, Waltz did not abandon the recognisable steps and leaps of the characters in Nijinsky’s ritualistic plot, seemingly so ridiculous to audiences in the early 20th century. In her Sacre one can also see recollections of Pina Bausch’s cult production – earth scattered on the stage and the striking dress in which the victim is “marked out”. Sasha Waltz, in using brief reminiscent symbols that remind us of themes touched on in earlier productions, has created her own story within the context of the ideas of those who came before her.

Her story is about human society. From the initial and serene harmony of Adam and Eve it comes to chaos and the necessity of a victim. And the mound of earth in the centre of the stage in the first scene is a kind of embodiment of nature, inherent harmony which will be trampled upon. On the other hand, this mound of earth is a reminder of the inevitability of sacrifice and death, as the sacrificial stake or the sword is slowly lowered over them during the performance – a sacrificial emblem.

Waltz does not separate any of society’s worries or aggressions. The performers in her production depict various social groups: couples, families, mankind in general. But that doesn’t bring harmony, it doesn’t stop the cruelty. The women who carry the thread of life, as if sensing the power that nature has given them, come together – here we see the motif of the battle of the sexes. Whatever society anyone may belong to resistance is inherent in human society’s forms, and independent of how society is structured there are inevitable and powerful shocks that Sasha Waltz expresses in movement: an organised mass that repeats one and the same movement in monotones, “expresses” and disperses in the chaos of individuals’ movements. The cataclysms that are experienced bring suffering to all – including children (Waltz includes some children in her narrative). In order to save and cure society a sacrifice must be made.

Waltz heard anxiety in Stravinsky’s rhythm and in her reading of the score of Le Sacre, following the cyclical nature of the music, she supercharges this anxiety with the composition and graphic position of the ensemble (the crowd is the main character in her production), the kaleidoscopic changes of distinct geometric structures against the background of the confusing chaos of worry, there is anxiety and there are nervous “sparks” in the movements. Just like Pina Bausch, the German Sasha Waltz depicts numerous accidental victims of aggression. She does not justify society. Yet her production of Le Sacre, as with Stravinsky and as Nijinsky conceived, remains a spring of hope for revival. This is not the optimism of Béjart’s Sacre with its hymn of love and belief in the power of unity. There is a victim who dies in the finale of Waltz’ version. She is not a chance victim of nature – she is sought out and pitied. She is one of that society and turns out to be resistant to it – she is the individual facing the masses. Her final monologue is a powerful energetic explosion which brings hope with the sheer power of its temper. All of the incandescent energy built up throughout the plot bursts out in this “final word”, and its power is bewitching, bringing us – if not to catharsis – to amazement at the power Sasha Waltz has managed to recreate on the stage.

Olga Makarova

For any choreographer of the 21st century creating their own Sacre, the importance of the great productions of their predecessors and their significance on the world scale makes citations all but inevitable. Sasha Waltz’s production also includes numerous references to masterpieces of the past. In creating her own version in the year of the work’s centenary, Waltz did not abandon the recognisable steps and leaps of the characters in Nijinsky’s ritualistic plot, seemingly so ridiculous to audiences in the early 20th century. In her Sacre one can also see recollections of Pina Bausch’s cult production – earth scattered on the stage and the striking dress in which the victim is “marked out”. Sasha Waltz, in using brief reminiscent symbols that remind us of themes touched on in earlier productions, has created her own story within the context of the ideas of those who came before her.

Her story is about human society. From the initial and serene harmony of Adam and Eve it comes to chaos and the necessity of a victim. And the mound of earth in the centre of the stage in the first scene is a kind of embodiment of nature, inherent harmony which will be trampled upon. On the other hand, this mound of earth is a reminder of the inevitability of sacrifice and death, as the sacrificial stake or the sword is slowly lowered over them during the performance – a sacrificial emblem.

Waltz does not separate any of society’s worries or aggressions. The performers in her production depict various social groups: couples, families, mankind in general. But that doesn’t bring harmony, it doesn’t stop the cruelty. The women who carry the thread of life, as if sensing the power that nature has given them, come together – here we see the motif of the battle of the sexes. Whatever society anyone may belong to resistance is inherent in human society’s forms, and independent of how society is structured there are inevitable and powerful shocks that Sasha Waltz expresses in movement: an organised mass that repeats one and the same movement in monotones, “expresses” and disperses in the chaos of individuals’ movements. The cataclysms that are experienced bring suffering to all – including children (Waltz includes some children in her narrative). In order to save and cure society a sacrifice must be made.

Waltz heard anxiety in Stravinsky’s rhythm and in her reading of the score of Le Sacre, following the cyclical nature of the music, she supercharges this anxiety with the composition and graphic position of the ensemble (the crowd is the main character in her production), the kaleidoscopic changes of distinct geometric structures against the background of the confusing chaos of worry, there is anxiety and there are nervous “sparks” in the movements. Just like Pina Bausch, the German Sasha Waltz depicts numerous accidental victims of aggression. She does not justify society. Yet her production of Le Sacre, as with Stravinsky and as Nijinsky conceived, remains a spring of hope for revival. This is not the optimism of Béjart’s Sacre with its hymn of love and belief in the power of unity. There is a victim who dies in the finale of Waltz’ version. She is not a chance victim of nature – she is sought out and pitied. She is one of that society and turns out to be resistant to it – she is the individual facing the masses. Her final monologue is a powerful energetic explosion which brings hope with the sheer power of its temper. All of the incandescent energy built up throughout the plot bursts out in this “final word”, and its power is bewitching, bringing us – if not to catharsis – to amazement at the power Sasha Waltz has managed to recreate on the stage.

Olga Makarova

You may also like

-

The Nutcracker (Hermitage Theatre, ballet)

Hermitage Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Nutcracker (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Nutcracker (Alexandrinsky Theatre, ballet)

Alexandrinsky Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Swan Lake (Carnival Concert Hall, ballet)

Carnival Concert Hall- Genre: Ballet

-

The Nutcracker (Mariinsky II New Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Nutcracker (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Carmen Suite. Sacre (Mariinsky II New Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Little Humpbacked Horse (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Die Fledermaus (Mariinsky II (New) Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Don Pasquale (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Les contes d'Hoffmann (semi-staged performance) (Mariinsky II (New) Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Sleeping Beauty (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Swan Lake (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Le Corsaire (Mariinsky II New Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Spartacus (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Die Puppenfee (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Don Quixote (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Romeo and Juliet (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Les Noces. Pulcinella. Jeu de cartes (premiere) (Mariinsky II (New) Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Swan Lake (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Giselle (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Le Corsaire (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Giselle, ou Les Wilis (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Don Quixote (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Young Lady and the Hooligan. Le Carnaval (Mariinsky II New Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky II (New) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Notre-Dame de Paris (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Paquita (Mariinsky Theatre, ballet)

Mariinsky (ex. Kirov) Ballet and Opera Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

La Fille mal gardée (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Multiplicity. Forms of Silence and Emptiness (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Laurencia (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

The Flames of Paris (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Cinderella (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Romeo and Juliet (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

La Bayadère (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

-

Without Words. Duende. White Darkness (Mikhailovsky Theatre, ballet)

Mikhailovsky (ex. Mussorgsky) Theatre- Genre: Ballet

en

en es

es